Author: Kathleen Flynn

In his examination of the great mystery of existence, the poet Tomas Tranströmer delights in exploring dualities: sleep and waking, past and present, the distance of far-away frontiers and the intimacy of everyday objects. One of the most frequently visited of these dualities in his work is the constant juxtaposition of the human made world with the natural world. In the opening lines of “The Nightingale in Badelunda”:

In the green midnight at the nightingale’s northern limit. Heavy leaves hang in trance, the deaf cars race towards the neon-line. The nightingale’s voice rises without wavering to the side, it is as penetrating as a cock-crow, but beautiful and free of vanity.

the concrete image of the “deaf cars” racing forward is enrobed in elements from the natural world. In brief strokes, Tranströmer evokes a time and space (midnight, midsummer, Sweden) and the vividness of the natural (green, heavy leaves, the nightingale). The blind cars (and by extension, humanity) rush by, unaware of the possibility of green liveliness.

Badelunda is an ancient Viking memorial and burial ground; the dead slumber under the heavy leaves, unaware of the passage of time

…Time streams down from the sun and the moon and into all the tick-tock-thankful clocks. But right here there is no time. Only the nightingale’s voice, the raw resonant notes that whet the night sky’s gleaming scythe.

But the poet stops and listens to the nightingale:

…I was In prison and it visited me. I was sick and it visited me. I didn’t

notice it then, but I do now.

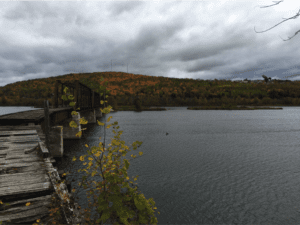

Badelunda, Sweden

suggesting that perhaps by allowing ourselves to become more aware of the natural world we can find a solace that is always waiting and available to us.

Throughout Tranströmer’s work we find the grounding presence of Nature. Through Nature, we find our best selves and the path to our humanity. Tranströmer balances the human made world with the natural world, but the borders dissolve and are liminal. He often transforms concrete objects into sprouting, living things. From “Lamento”:

Outside it is early summer.

From the greenery come whistlings – men or birds?

And cherry trees in bloom embrace the lorries which have come home.

In “Further In”, the traffic becomes a dragon transporting the reader from the city to the forest:

The traffic thickens, crawls.

It is a sluggish dragon glittering.

I am one of the dragon’s scales.

The poet feels the pull of the forest:

I know I must get far away

straight through the city and then

further until it is time to go out

and walk far in the forest.

It is in the forest and surrounded by the natural world of the forest, badgers, and moss, that the poet finds the possibility of enlightenment:

One of the stones is precious.

it can change everything

it can make the darkness shine.

It is a switch for the whole country.

Everything depends on it.

Look at it, touch it…

Woodstock, NB

In “Preludes II”, there are two truths that approach each other:

...One comes from inside, one comes from outside

And where they meet we have a chance to see ourselves.

We then encounter this startling image:

Out of the forest gloom comes a long boat-hook, it is pushed in through the open window,

In among the party guests who danced themselves warm.

It is a truth approaching from the natural word into the constructed world. Tranströmer seems to exhort us to pay attention to the natural world, to allow it into our consciousness more readily. Through this awareness, we can more fully experience our connection to the natural world and illuminate a path towards a deeper humanity.

Translations of Tomas Tranströmer’s poetry are from New Collected Poems, translated by Robin Fulton, Bloodaxe Books, Newcastle upon Tyne, 1997.

Oslo, Norway

Recent Comments